Who is Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal

the billionaire investor behind Four Seasons & Fairmont Hotels

Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal

Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal

“Hotels are on the way up; they’re taking off,” says Alwaleed.

Alwaleed, 55, one of the world’s richest men, saw his net worth climb to $21.1 billion in May 2000, according to his tally of investments and personal wealth. He achieved that mostly by investing in big-name companies such as Apple Inc. and News Corp.

Since then, many stocks have turned against him, especially those of Citigroup Inc. and Time Warner Inc. The Saudi royal’s fortune has been trimmed to $16.6 billion, based on the value of his Kingdom Holding Co. stake on March 31 and his personal assets as of Feb. 10.

‘Buffett of Arabia’

Alwaleed often refers to himself as the “Buffett of Arabia,” although the comparison to Warren Buffett, chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., doesn’t hold up. Berkshire Hathaway’s Class A shares more than doubled in the same span of almost ten years, swelling Buffett’s stake to $48.7 billion.

Alwaleed, who’s a nephew of Saudi King Abdullah, is plotting a rebound. The prince’s Riyadh-based Kingdom Holding, which invests most of his wealth, has been retreating from U.S. equities and pouring billions into luxury hotels and large-scale housing and commercial developments in Saudi Arabia and around the world.

Kingdom Holding, where Alwaleed serves as chairman, has boosted its property-related assets, such as Four Seasons Hotels Inc., to 75 percent of its holdings, according to his company’s 2009 annual report. Publicly traded stock, which made up at least 79 percent of Alwaleed’s assets in 2000, now constitutes only about 23 percent of his wealth.

Kingdom Holding, where Alwaleed serves as chairman, has boosted its property-related assets, such as Four Seasons Hotels Inc., to 75 percent of its holdings, according to his company’s 2009 annual report. Publicly traded stock, which made up at least 79 percent of Alwaleed’s assets in 2000, now constitutes only about 23 percent of his wealth.

371-Room Palace

Alwaleed’s most ambitious undertaking is the 1-kilometer- tall (0.62-mile-tall) Kingdom Tower in Jeddah. When completed, the skyscraper will be the world’s tallest, surpassing the current record holder -- Dubai’s Burj Khalifa -- by 21 percent.

The prince says his shift in strategy at Kingdom Holding, which he controls with a 95 percent stake, may put him on a path to surpass the riches of the 79-year-old Buffett.

“When he was my age, he was not as big as me,” Alwaleed says. “I still have 20 years.”

Alwaleed’s preoccupation with his status and wealth, which includes four jets, a 281-foot (86-meter) yacht and a 371-room palace, is also on display at Kingdom Holding’s headquarters.

Alwaleed’s preoccupation with his status and wealth, which includes four jets, a 281-foot (86-meter) yacht and a 371-room palace, is also on display at Kingdom Holding’s headquarters.

The glass tower that he built has an oval-shaped hole in the top that resembles the eye of a sewing needle. In his 66th- floor office, models of his airplanes decorate his desk. Bookshelves display reprints of magazine articles about his ranking on billionaire lists.

Bill Gates

The prince keeps meticulous track of the ups and downs of his fortune, Kingdom Holding Chief Financial Officer Shadi Sanbar says.

Alwaleed hires appraisers to value his private assets -- such as a jewelry collection worth more than $700 million -- and makes those figures available to publishers of rich lists, Sanbar says. After a ranking is published, the prince sometimes issues a press release touting his position.

“He wants to be the best, the wealthiest; that by itself is what motivates him,” says Saleh Al Fadl, who worked for Alwaleed from 1989 to 1993 at United Saudi Commercial Bank, one of the prince’s earliest investments, and now helps run retail banking at Riyadh-based Saudi Hollandi Bank.

In addition to chasing Buffett, Alwaleed has also been preoccupied with Bill Gates, the Microsoft Corp. founder who has often topped the billionaire rankings, Al Fadl says. “He was always referring to Bill Gates,” he says.

Buffett Letters

Alwaleed is particularly fond of his correspondence with Buffett by mail and fax over a span of at least nine years.

Alwaleed is particularly fond of his correspondence with Buffett by mail and fax over a span of at least nine years.

Buffett started the exchange, writing Alwaleed after a 12- day stay at New York’s Plaza Hotel. In the May 1999 letter, Buffett called the Plaza his “home” when in New York and praised the prince, who then owned a 42 percent stake in the hotel, for the extraordinary service.

“You have restored The Plaza to its former luster -- indeed your managers have enabled it to surpass its previous heights -- and I congratulate you,” Buffett wrote in the first of a series of letters that Alwaleed gave to Bloomberg News.

The prince responded a month later, saying he was elated to have an individual of such discriminating tastes attest to the Plaza’s high standards. Alwaleed then got down to business.

“Needless to say, I should be pleased to consider participating in any of your future investments that you may deem pertinent,” the prince wrote.

A Laggard

Buffett, who grew rich by investing in consumer brands such as American Express Co. and Coca-Cola Co., wrote back three days later. He said he would be delighted to team up with the prince. He also piled on the praise.

“In Omaha, I’m known as the ‘Alwaleed of America’ -- which is quite a compliment,” Buffett wrote.

In December 1999, Alwaleed told Buffett in a letter that he found news coverage of a slump in Berkshire’s stock “highly objectionable” and had written to editors to defend him.

“Dear Prince Alwaleed,” Buffett responded the next day. “You’re terrific!”

A decade later, it’s the prince’s investments that need a boost. As of March 31, Alwaleed’s net worth had dropped 21 percent from May 2000, the tally shows.

Citigroup shares, which fell 90 percent during the period, did the most damage to his fortune. The prince even fell behind the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which returned 27 percent, including reinvested dividends.

“He’s become a laggard,” says Laszlo Birinyi, founder of equity research firm Birinyi Associates Inc. in Westport, Connecticut. “As an investor, his record is not worth following.”

Unrealized Losses

Sitting at his gray-marble desk in his office, Alwaleed defends his stock picking, saying most of his losses came in 2008 as a wave of subprime-mortgage defaults convulsed the financial world.

He grabs a copy of Richard J. Connors’s book “Warren Buffett on Business” (Wiley, 2009) and flips it open to a passage he has highlighted with a green marker. It describes Berkshire Hathaway’s assets declining in 2008, reducing the book value of the company’s shares by 9.6 percent.

He grabs a copy of Richard J. Connors’s book “Warren Buffett on Business” (Wiley, 2009) and flips it open to a passage he has highlighted with a green marker. It describes Berkshire Hathaway’s assets declining in 2008, reducing the book value of the company’s shares by 9.6 percent.

“Just read this,” he says. “Look what it says. In 2008, everyone had a hiccup. He went down also.”

Buffett declined to comment for this story.

Alwaleed’s decline may be worse than his accounting shows. In its 2008 annual report, Kingdom Holding classified more than $4 billion of its $7.45 billion of stock market losses as temporary -- and therefore didn’t subtract them from its earnings.

Ernst & Young Note

Kingdom Holding’s auditor in Riyadh, Ernst & Young, qualified its approval of the accounts, saying it couldn’t determine whether the company took a big enough deduction for the market losses, according to its notes on the company’s statements. Ernst & Young didn’t say the company had violated accounting standards generally accepted in Saudi Arabia.

Kingdom Holding’s auditor in Riyadh, Ernst & Young, qualified its approval of the accounts, saying it couldn’t determine whether the company took a big enough deduction for the market losses, according to its notes on the company’s statements. Ernst & Young didn’t say the company had violated accounting standards generally accepted in Saudi Arabia.

A year later, as the unrealized loss shrank to $3.53 billion, Ernst & Young didn’t attach any qualification to its audit of Kingdom Holding.

Even though the unrealized loss has come down, the auditor’s notes suggest that the value of Kingdom Holding may be less than its market capitalization of $9.49 billion as of April 26, says Steven Bankler, a San Antonio-based forensic accountant who examined the company’s financial statements at the request of Bloomberg News.

Kingdom Holding’s Sanbar says the company correctly judged the size of its unrealized loss and that it expects its stock investments to bounce back.

Kingdom Oasis

Alwaleed also hopes to boost his fortune in the desert of Saudi Arabia. Northeast of Riyadh, the prince’s armored GMC Suburban bumps over rocks as he prepares to inspect his latest project: Kingdom Oasis, a development that includes an equestrian resort, a banquet facility and villas. Oasis is part of the 16.8-square-kilometer (6.5-square-mile) Kingdom City Riyadh planned community.

His driver, who has a black pistol holstered under his arm, turns past what will be a safari park and lake and stops in front of a clubhouse next to horse stables.

Alwaleed ducks inside the clubhouse and spots a flaw: Two Ping-Pong tables in the recreation room instead of one. He thrusts his wooden walking stick at one of the tables.

“This should be removed,” he barks at his project managers. “And put in billiards.”

When he’s not inspecting his investments, Alwaleed sometimes meets with foreign officials and heads of state as part of his role as a Saudi royal.

Saudi King

“I’m a businessman, but that’s only a platform,” he says. When asked if he wants to be king, he said he would serve his nation in any capacity if asked.

In a country with thousands of princes and an autocratic regime with no firm order of succession, Alwaleed doesn’t have a clear path to the throne. Unlike his cousins from other lines of the Saud family, he lacks a formal role in government.

Alwaleed’s father, Talal Bin Abdulaziz, does sit on the kingdom’s commission for succession, which helps pick the crown prince after the death of a king.

Alwaleed’s father, Talal Bin Abdulaziz, does sit on the kingdom’s commission for succession, which helps pick the crown prince after the death of a king.

Talal became a black sheep of the royal clan after pressing unsuccessfully in the 1950s for more democracy in Saudi Arabia. He later founded the Arab Gulf Program for United Nations Development Organizations in 1980 and currently serves as its president. The group raises money to support reproductive health education in Mauritania and women’s entrepreneurship in the Gaza Strip.

Princess Ameerah Altaweel

Alwaleed has followed his father’s example by advocating for greater freedom for Saudi women, who must wear neck-to-toe robes to mask their figures in public.

The prince has hired a mostly female staff at his offices, creating workplaces rarely seen in Saudi Arabia. The women he employs dress in Western clothing and hold jobs managing his construction projects, piloting his jets and directing catering at his palace.

Three times divorced, the prince has a son, 32, and a daughter, 27. Alwaleed is now married to Princess Ameerah Altaweel, 27, who speaks fluent English with an American accent she picked up from watching the television show “Friends.”

Three times divorced, the prince has a son, 32, and a daughter, 27. Alwaleed is now married to Princess Ameerah Altaweel, 27, who speaks fluent English with an American accent she picked up from watching the television show “Friends.”

The princess, who’s vice chairman of the Alwaleed Bin Talal Foundations for Charity and Philanthropy, says she wants to be the first Saudi woman to drive on public roads -- if it becomes legal.

“She’s the vanguard,” Alwaleed says.

Starting with $30,000

The prince says his liberal views were nurtured in the U.S., where in 1979 he received an undergraduate degree in business administration from Menlo College in Atherton, California.

After Alwaleed returned to Riyadh, his father jump-started the prince’s investment career by giving him a $30,000 loan and a house, which he mortgaged. As the prince started to build his fortune, he earned a master’s degree in social science from Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York, in 1985.

Alwaleed says he made his first billion by 1989 from investments in Saudi real estate and banking as well as commissions he earned as a local agent for foreign construction companies. In the next two years, the prince began investing in Citicorp, which was then drowning in bad real estate loans.

After Citicorp Chief Executive Officer John Reed asked Alwaleed for a cash infusion, the prince in 1991 added $590 million to his stake. That brought his total investment to $797 million, making him the bank’s biggest individual shareholder -- a position the prince says he still holds today.

Technology Splurge

Seven years later, the bank merged with Travelers Group Inc. to form Citigroup, and by 2000, Alwaleed’s shares were worth $8.6 billion, even after he’d sold off some of his original holding.

Seven years later, the bank merged with Travelers Group Inc. to form Citigroup, and by 2000, Alwaleed’s shares were worth $8.6 billion, even after he’d sold off some of his original holding.

“He took a big risk and it paid off,” says David Webb, head of the finance department at the London School of Economics. “Big fund managers didn’t buy the stock, and then some guy from the Middle East puts all his eggs in one basket. We all could have been rich, looking backwards.”

The billionaire used his new riches to splurge on U.S. technology shares in the first half of 2000. Just as stock markets were beginning to plunge that year, with the Nasdaq Composite Index falling 78 percent through October 2002, Alwaleed bought $400 million of Compaq Computer Corp. shares and $200 million of WorldCom Inc.

He also purchased shares of Amazon.com Inc. and DoubleClick Inc. as well as household names such as AT&T Corp., McDonald’s Corp. and Coca-Cola. The prince told Bloomberg News at the time that he was buying all of these stocks on the cheap.

Praise from Murdoch

As he spread his money around corporate America, Alwaleed won many friends. News Corp. Chairman Rupert Murdoch was among the 355 guests who gathered at the Plaza Hotel to honor the prince in November 2000 at an awards dinner thrown by the Arab Bankers Association of North America.

As he spread his money around corporate America, Alwaleed won many friends. News Corp. Chairman Rupert Murdoch was among the 355 guests who gathered at the Plaza Hotel to honor the prince in November 2000 at an awards dinner thrown by the Arab Bankers Association of North America.

After the guests took their seats in the Grand Ballroom, Alwaleed entered the room with his retinue and walked to the head table, drawing applause. He sat next to Murdoch, and the two men chatted over a dinner of lobster tails and rack of lamb.

Then the media mogul took the podium to praise the Saudi royal for his investment in News Corp., at the time an Australian company that had U.S.-traded shares. From his initial News Corp. investments of a combined $600 million in 1997 and 1999 through that evening in 2000, Alwaleed had almost doubled his money.

“Very proud, we are, that Prince Alwaleed is one of News Corp.’s largest shareholders,” Murdoch said.

Selling Apple

After six tribute speeches, Alwaleed returned to the hotel’s Suite 537, decorated with gilded furniture, where journalists quizzed him about ill-timed investments he had announced about six months earlier.

After six tribute speeches, Alwaleed returned to the hotel’s Suite 537, decorated with gilded furniture, where journalists quizzed him about ill-timed investments he had announced about six months earlier.

“We don’t see any further investments in the Internet,” Alwaleed said. “Many companies are going to go bankrupt.”

In 2002, the same year in which WorldCom went belly up, the prince deployed another $1 billion in three companies whose stock he already owned: AOL Time Warner Inc., Priceline.com Inc. and Citigroup.

Priceline.com was the only winner: The shares he’s held on to have jumped fourfold to about $175 million, based on data in Kingdom Holding documents.

The investor would be worth several billion dollars more today had he not chucked the bulk of his stake in Apple in 2005. He had poured $115 million into the computer maker in 1997. Under founder and CEO Steve Jobs, the company introduced the iPod four years later.

Returning to Saudi

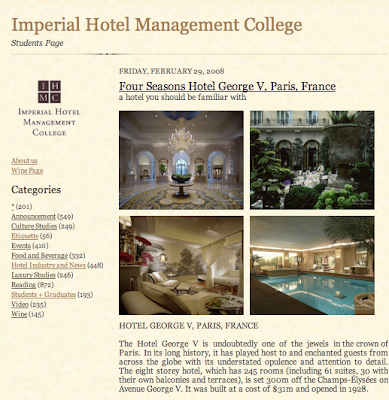

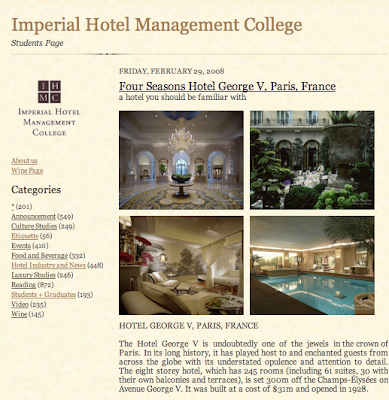

At Alwaleed’s Hotel George V in Paris in November 2005, the prince told Bloomberg News his motive for selling his Apple stake.

At Alwaleed’s Hotel George V in Paris in November 2005, the prince told Bloomberg News his motive for selling his Apple stake.

“The benefit of iTunes and all the good moves that Steve Jobs has done have already been put in the price,” Alwaleed said.

He was wrong. The rapidly selling iPod was followed in 2007 by the iPhone, which transformed mobile devices, and the iPad in 2010. The prince missed a sevenfold rally starting from the middle of 2005. His holding would have been worth about $6.75 billion as of today.

As Alwaleed was selling his Apple shares, he began moving money from the U.S. into Saudi Arabia, which itself was in transition. In 2005, King Fahd, who had ruled for 23 years, died at age 82, propelling Alwaleed’s uncle -- Crown Prince Abdullah -- to the throne.

“The prince made a commitment to the king,” Sanbar, 62, says. “He said, ‘Instead of having 80 percent of my wealth outside, I’m going to bring it here.’”

Kingdom IPO

In 2007, Alwaleed put together an initial public offering for Kingdom Holding on the Saudi stock exchange. The 240-page prospectus, which appeared on Kingdom Holding’s Web site only in Arabic, said the company’s listed assets had achieved lifetime annual returns of 19.9 percent through March 30, 2007.

In 2007, Alwaleed put together an initial public offering for Kingdom Holding on the Saudi stock exchange. The 240-page prospectus, which appeared on Kingdom Holding’s Web site only in Arabic, said the company’s listed assets had achieved lifetime annual returns of 19.9 percent through March 30, 2007.

The figure included only shares held at the time, omitting money losers such as WorldCom that Alwaleed had already sold.

“These historical results do not represent all of the investments that Management has made during the relevant historical periods,” the prospectus said.

The prospectus contained one number that concerned potential shareholders, Sanbar says. Some 40 percent of its assets were in Citigroup stock, which was just starting to slip from its record high of $56.41 in December 2006. Kingdom Holding assured investors it would pare back the Citigroup stake.

“The answer was, we were going to start selling and shift to regional and Gulf investments,” Sanbar says.

Citigroup Crashes

Kingdom Holding’s stock jumped 20 percent on its first day of trading on July 29, 2007, giving the company a market value of about $20 billion. But Kingdom never sold its Citigroup shares as planned. From the IPO to the end of 2007, as credit markets tightened, the bank’s stock plunged by more than a third.

Kingdom Holding’s stock jumped 20 percent on its first day of trading on July 29, 2007, giving the company a market value of about $20 billion. But Kingdom never sold its Citigroup shares as planned. From the IPO to the end of 2007, as credit markets tightened, the bank’s stock plunged by more than a third.

“Buy-and-forget can be deadly to a portfolio,” says Frederic Dickson, who manages $25 billion, including Citigroup shares, as chief market strategist at D.A. Davidson & Co. in Lake Oswego, Oregon.

As the deepening credit crisis sent Citigroup shares tumbling 77 percent in 2008, Alwaleed had one reason to cheer. At Microsoft’s annual CEO summit in May in Redmond, Washington, the prince finally got to meet his pen pal, Buffett.

During the event, a beaming Alwaleed posed with Buffett for a photo taken by the prince’s personal photographer. Buffett hammed it up for the camera, handing his black wallet to the prince as the flash went off.

Photo With Buffett

After the conference, Alwaleed sent Buffett a copy of the photo, and Buffett wrote back to thank the prince. In signing off, he continued their banter about collaborating.

After the conference, Alwaleed sent Buffett a copy of the photo, and Buffett wrote back to thank the prince. In signing off, he continued their banter about collaborating.

“I hope we can come up with something in which we can work together,” Buffett said in the June 2008 letter.

Alwaleed could use some help from the Oracle of Omaha. In 2008, Kingdom Holding reported a net loss of $7.98 billion. That year, as the U.S. government injected $45 billion into Citigroup to save it, the prince began to buy more of the bank’s shares.

“At $3, you have to buy,” Alwaleed says. His purchases from 2008 and 2009 turned a profit as Citigroup shares rose to $4.61 on April 26.

While Kingdom Holding rebounded to a profit of $107 million for 2009, it also reported the unrealized loss of $3.53 billion that carried over from 2008’s rout. Bankler, the forensic accountant, says the profit could vanish, slashing the company’s market value and Alwaleed’s net worth, if even a small portion of those unrealized losses became permanent.

Fairmont, Four Seasons

“One of the factors of market value is earnings per share, and they didn’t take that hit,” Bankler says.

“One of the factors of market value is earnings per share, and they didn’t take that hit,” Bankler says.

Alwaleed’s fortunes are improving this year. On April 19, Citigroup posted a first-quarter profit after two years of losses, and the next day, Kingdom Holding also reported a gain. But the company’s shares remain in the doldrums. Since its first trading day in 2007, Kingdom Holding’s stock has fallen 54 percent to 9.6 Saudi riyals on April 26.

“Alwaleed is a major player, always will be,” says Four Seasons CEO Isadore Sharp, who became fast friends with the prince after they met on Alwaleed’s yacht in 1994. “The markets are turning. Things are getting back on track.”

Alwaleed says he plans to take his hotel businesses public in the next few years. He bought his first stakes in Toronto- based Fairmont Raffles Holdings International and Four Seasons in 1994. Fairmont also runs the Plaza Hotel, which is jointly owned by Kingdom Holding and Israeli billionaire Isaac Tshuva’s Elad Properties.

Hotels made up 63 percent of the assets in the prince’s company in 2009, according to its year-end report.

‘He’s a Hotelier’

“He’s a hotelier,” Bankler says. “This is a hotel company.”

Alwaleed’s partners in Fairmont, which runs more than 90 hotels worldwide, include Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund and Colony Capital LLC, the Los Angeles-based buyout firm founded by billionaire Thomas J. Barrack.

The prince is in business with Gates at Four Seasons, which operates 83 hotels globally. Kingdom Holding and Gates’s investment company, Cascade Investment LLC, each hold 47.5 percent of the hotel management company. Sharp, who founded Four Seasons, retains a 5 percent stake.

Fairmont and Four Seasons may be ripe for an IPO as the recession eases and companies stop trimming travel expenses, says Smedes Rose, an analyst who covers hotels at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc. in New York.

Kingdom Tower

“Trends are turning much better for them, and you’d want to go public into the momentum of a recovering market,” he says. “Four Seasons has a lot of legs.”

“Trends are turning much better for them, and you’d want to go public into the momentum of a recovering market,” he says. “Four Seasons has a lot of legs.”

Alwaleed says that within two years he also plans to hold an IPO for his Riyadh-based media company, Rotana Holding, which includes Arabic movie and music channels and a record label. In February, Murdoch’s News Corp. agreed to buy 9.1 percent of Rotana for $70 million.

The prince’s Kingdom Tower project in Jeddah, Saudi’s commercial hub on the Red Sea, faces several obstacles. The spike-shaped skyscraper anchors a project that includes shopping malls, a marina, hotels, villas and parks. Alwaleed, who says the tower will be completed in four to five years, plans to raise some of the $20 billion that the complex will cost from equity investors and the sale of Islamic bonds.

And he has hired Emaar Properties PJSC -- the Dubai-based contractor that erected Burj Khalifa -- to manage the project.

And he has hired Emaar Properties PJSC -- the Dubai-based contractor that erected Burj Khalifa -- to manage the project.

“The beef is in Saudi Arabia,” Alwaleed says. “In 2010, we’re seeing ourselves coming out of it.”

Burj Khalifa opened in January, just after the Arab emirate went from being the world’s best-performing real estate market to the worst. Prices for apartments in the tower have dropped to less than half of their 2008 peak during the credit crackup.

$32.1 Billion Difference

Alwaleed may have an even tougher time filling his skyscraper in Saudi Arabia, says Saud Masud, head of Middle East research at UBS AG in Dubai. Masud says Saudi laws and customs, including restrictions on travel, women’s attire and the purchase of local securities by foreigners, deter visitors and businesses from entering the nation.

“It’s not going to be a straightforward build-it-and-they- will-come,” Masud says. “What the market needs now is affordable housing and not kilometer towers.”

As the prince rides in his GMC truck around the site of his Kingdom City residential development, he once again draws comparisons between himself and Buffett: The prince says they both buy undervalued assets. The offices of Kingdom Holding and Berkshire Hathaway have roughly the same square footage, and both companies have small staffs at their headquarters.

Pepsi Versus Coke

“I drink Pepsi; he drinks Coke,” Alwaleed says, with a laugh.

The biggest difference between the two men: The investor from Omaha is worth about $32.1 billion more than the Saudi prince. Alwaleed’s sluggish performance over the past decade hasn’t crimped his style, though.

In 2012, he’ll take delivery of a custom-fitted double- decker Airbus A380, becoming the first private buyer of the world’s biggest airliner. While he may not be the world’s richest man, he knows how to act like he is.

In 2012, he’ll take delivery of a custom-fitted double- decker Airbus A380, becoming the first private buyer of the world’s biggest airliner. While he may not be the world’s richest man, he knows how to act like he is.

Source:

Bloomberg

Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal

Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal“Hotels are on the way up; they’re taking off,” says Alwaleed.

Alwaleed, 55, one of the world’s richest men, saw his net worth climb to $21.1 billion in May 2000, according to his tally of investments and personal wealth. He achieved that mostly by investing in big-name companies such as Apple Inc. and News Corp.

Since then, many stocks have turned against him, especially those of Citigroup Inc. and Time Warner Inc. The Saudi royal’s fortune has been trimmed to $16.6 billion, based on the value of his Kingdom Holding Co. stake on March 31 and his personal assets as of Feb. 10.

‘Buffett of Arabia’

Alwaleed often refers to himself as the “Buffett of Arabia,” although the comparison to Warren Buffett, chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., doesn’t hold up. Berkshire Hathaway’s Class A shares more than doubled in the same span of almost ten years, swelling Buffett’s stake to $48.7 billion.

Alwaleed, who’s a nephew of Saudi King Abdullah, is plotting a rebound. The prince’s Riyadh-based Kingdom Holding, which invests most of his wealth, has been retreating from U.S. equities and pouring billions into luxury hotels and large-scale housing and commercial developments in Saudi Arabia and around the world.

Kingdom Holding, where Alwaleed serves as chairman, has boosted its property-related assets, such as Four Seasons Hotels Inc., to 75 percent of its holdings, according to his company’s 2009 annual report. Publicly traded stock, which made up at least 79 percent of Alwaleed’s assets in 2000, now constitutes only about 23 percent of his wealth.

Kingdom Holding, where Alwaleed serves as chairman, has boosted its property-related assets, such as Four Seasons Hotels Inc., to 75 percent of its holdings, according to his company’s 2009 annual report. Publicly traded stock, which made up at least 79 percent of Alwaleed’s assets in 2000, now constitutes only about 23 percent of his wealth.371-Room Palace

Alwaleed’s most ambitious undertaking is the 1-kilometer- tall (0.62-mile-tall) Kingdom Tower in Jeddah. When completed, the skyscraper will be the world’s tallest, surpassing the current record holder -- Dubai’s Burj Khalifa -- by 21 percent.

The prince says his shift in strategy at Kingdom Holding, which he controls with a 95 percent stake, may put him on a path to surpass the riches of the 79-year-old Buffett.

“When he was my age, he was not as big as me,” Alwaleed says. “I still have 20 years.”

Alwaleed’s preoccupation with his status and wealth, which includes four jets, a 281-foot (86-meter) yacht and a 371-room palace, is also on display at Kingdom Holding’s headquarters.

Alwaleed’s preoccupation with his status and wealth, which includes four jets, a 281-foot (86-meter) yacht and a 371-room palace, is also on display at Kingdom Holding’s headquarters.The glass tower that he built has an oval-shaped hole in the top that resembles the eye of a sewing needle. In his 66th- floor office, models of his airplanes decorate his desk. Bookshelves display reprints of magazine articles about his ranking on billionaire lists.

Bill Gates

The prince keeps meticulous track of the ups and downs of his fortune, Kingdom Holding Chief Financial Officer Shadi Sanbar says.

Alwaleed hires appraisers to value his private assets -- such as a jewelry collection worth more than $700 million -- and makes those figures available to publishers of rich lists, Sanbar says. After a ranking is published, the prince sometimes issues a press release touting his position.

“He wants to be the best, the wealthiest; that by itself is what motivates him,” says Saleh Al Fadl, who worked for Alwaleed from 1989 to 1993 at United Saudi Commercial Bank, one of the prince’s earliest investments, and now helps run retail banking at Riyadh-based Saudi Hollandi Bank.

In addition to chasing Buffett, Alwaleed has also been preoccupied with Bill Gates, the Microsoft Corp. founder who has often topped the billionaire rankings, Al Fadl says. “He was always referring to Bill Gates,” he says.

Buffett Letters

Alwaleed is particularly fond of his correspondence with Buffett by mail and fax over a span of at least nine years.

Alwaleed is particularly fond of his correspondence with Buffett by mail and fax over a span of at least nine years.Buffett started the exchange, writing Alwaleed after a 12- day stay at New York’s Plaza Hotel. In the May 1999 letter, Buffett called the Plaza his “home” when in New York and praised the prince, who then owned a 42 percent stake in the hotel, for the extraordinary service.

“You have restored The Plaza to its former luster -- indeed your managers have enabled it to surpass its previous heights -- and I congratulate you,” Buffett wrote in the first of a series of letters that Alwaleed gave to Bloomberg News.

The prince responded a month later, saying he was elated to have an individual of such discriminating tastes attest to the Plaza’s high standards. Alwaleed then got down to business.

“Needless to say, I should be pleased to consider participating in any of your future investments that you may deem pertinent,” the prince wrote.

A Laggard

Buffett, who grew rich by investing in consumer brands such as American Express Co. and Coca-Cola Co., wrote back three days later. He said he would be delighted to team up with the prince. He also piled on the praise.

“In Omaha, I’m known as the ‘Alwaleed of America’ -- which is quite a compliment,” Buffett wrote.

In December 1999, Alwaleed told Buffett in a letter that he found news coverage of a slump in Berkshire’s stock “highly objectionable” and had written to editors to defend him.

“Dear Prince Alwaleed,” Buffett responded the next day. “You’re terrific!”

A decade later, it’s the prince’s investments that need a boost. As of March 31, Alwaleed’s net worth had dropped 21 percent from May 2000, the tally shows.

Citigroup shares, which fell 90 percent during the period, did the most damage to his fortune. The prince even fell behind the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which returned 27 percent, including reinvested dividends.

“He’s become a laggard,” says Laszlo Birinyi, founder of equity research firm Birinyi Associates Inc. in Westport, Connecticut. “As an investor, his record is not worth following.”

Unrealized Losses

Sitting at his gray-marble desk in his office, Alwaleed defends his stock picking, saying most of his losses came in 2008 as a wave of subprime-mortgage defaults convulsed the financial world.

He grabs a copy of Richard J. Connors’s book “Warren Buffett on Business” (Wiley, 2009) and flips it open to a passage he has highlighted with a green marker. It describes Berkshire Hathaway’s assets declining in 2008, reducing the book value of the company’s shares by 9.6 percent.

He grabs a copy of Richard J. Connors’s book “Warren Buffett on Business” (Wiley, 2009) and flips it open to a passage he has highlighted with a green marker. It describes Berkshire Hathaway’s assets declining in 2008, reducing the book value of the company’s shares by 9.6 percent.“Just read this,” he says. “Look what it says. In 2008, everyone had a hiccup. He went down also.”

Buffett declined to comment for this story.

Alwaleed’s decline may be worse than his accounting shows. In its 2008 annual report, Kingdom Holding classified more than $4 billion of its $7.45 billion of stock market losses as temporary -- and therefore didn’t subtract them from its earnings.

Ernst & Young Note

Kingdom Holding’s auditor in Riyadh, Ernst & Young, qualified its approval of the accounts, saying it couldn’t determine whether the company took a big enough deduction for the market losses, according to its notes on the company’s statements. Ernst & Young didn’t say the company had violated accounting standards generally accepted in Saudi Arabia.

Kingdom Holding’s auditor in Riyadh, Ernst & Young, qualified its approval of the accounts, saying it couldn’t determine whether the company took a big enough deduction for the market losses, according to its notes on the company’s statements. Ernst & Young didn’t say the company had violated accounting standards generally accepted in Saudi Arabia.A year later, as the unrealized loss shrank to $3.53 billion, Ernst & Young didn’t attach any qualification to its audit of Kingdom Holding.

Even though the unrealized loss has come down, the auditor’s notes suggest that the value of Kingdom Holding may be less than its market capitalization of $9.49 billion as of April 26, says Steven Bankler, a San Antonio-based forensic accountant who examined the company’s financial statements at the request of Bloomberg News.

Kingdom Holding’s Sanbar says the company correctly judged the size of its unrealized loss and that it expects its stock investments to bounce back.

Kingdom Oasis

Alwaleed also hopes to boost his fortune in the desert of Saudi Arabia. Northeast of Riyadh, the prince’s armored GMC Suburban bumps over rocks as he prepares to inspect his latest project: Kingdom Oasis, a development that includes an equestrian resort, a banquet facility and villas. Oasis is part of the 16.8-square-kilometer (6.5-square-mile) Kingdom City Riyadh planned community.

His driver, who has a black pistol holstered under his arm, turns past what will be a safari park and lake and stops in front of a clubhouse next to horse stables.

Alwaleed ducks inside the clubhouse and spots a flaw: Two Ping-Pong tables in the recreation room instead of one. He thrusts his wooden walking stick at one of the tables.

“This should be removed,” he barks at his project managers. “And put in billiards.”

When he’s not inspecting his investments, Alwaleed sometimes meets with foreign officials and heads of state as part of his role as a Saudi royal.

Saudi King

“I’m a businessman, but that’s only a platform,” he says. When asked if he wants to be king, he said he would serve his nation in any capacity if asked.

In a country with thousands of princes and an autocratic regime with no firm order of succession, Alwaleed doesn’t have a clear path to the throne. Unlike his cousins from other lines of the Saud family, he lacks a formal role in government.

Alwaleed’s father, Talal Bin Abdulaziz, does sit on the kingdom’s commission for succession, which helps pick the crown prince after the death of a king.

Alwaleed’s father, Talal Bin Abdulaziz, does sit on the kingdom’s commission for succession, which helps pick the crown prince after the death of a king.Talal became a black sheep of the royal clan after pressing unsuccessfully in the 1950s for more democracy in Saudi Arabia. He later founded the Arab Gulf Program for United Nations Development Organizations in 1980 and currently serves as its president. The group raises money to support reproductive health education in Mauritania and women’s entrepreneurship in the Gaza Strip.

Princess Ameerah Altaweel

Alwaleed has followed his father’s example by advocating for greater freedom for Saudi women, who must wear neck-to-toe robes to mask their figures in public.

The prince has hired a mostly female staff at his offices, creating workplaces rarely seen in Saudi Arabia. The women he employs dress in Western clothing and hold jobs managing his construction projects, piloting his jets and directing catering at his palace.

Three times divorced, the prince has a son, 32, and a daughter, 27. Alwaleed is now married to Princess Ameerah Altaweel, 27, who speaks fluent English with an American accent she picked up from watching the television show “Friends.”

Three times divorced, the prince has a son, 32, and a daughter, 27. Alwaleed is now married to Princess Ameerah Altaweel, 27, who speaks fluent English with an American accent she picked up from watching the television show “Friends.”The princess, who’s vice chairman of the Alwaleed Bin Talal Foundations for Charity and Philanthropy, says she wants to be the first Saudi woman to drive on public roads -- if it becomes legal.

“She’s the vanguard,” Alwaleed says.

Starting with $30,000

The prince says his liberal views were nurtured in the U.S., where in 1979 he received an undergraduate degree in business administration from Menlo College in Atherton, California.

After Alwaleed returned to Riyadh, his father jump-started the prince’s investment career by giving him a $30,000 loan and a house, which he mortgaged. As the prince started to build his fortune, he earned a master’s degree in social science from Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York, in 1985.

Alwaleed says he made his first billion by 1989 from investments in Saudi real estate and banking as well as commissions he earned as a local agent for foreign construction companies. In the next two years, the prince began investing in Citicorp, which was then drowning in bad real estate loans.

After Citicorp Chief Executive Officer John Reed asked Alwaleed for a cash infusion, the prince in 1991 added $590 million to his stake. That brought his total investment to $797 million, making him the bank’s biggest individual shareholder -- a position the prince says he still holds today.

Technology Splurge

Seven years later, the bank merged with Travelers Group Inc. to form Citigroup, and by 2000, Alwaleed’s shares were worth $8.6 billion, even after he’d sold off some of his original holding.

Seven years later, the bank merged with Travelers Group Inc. to form Citigroup, and by 2000, Alwaleed’s shares were worth $8.6 billion, even after he’d sold off some of his original holding.“He took a big risk and it paid off,” says David Webb, head of the finance department at the London School of Economics. “Big fund managers didn’t buy the stock, and then some guy from the Middle East puts all his eggs in one basket. We all could have been rich, looking backwards.”

The billionaire used his new riches to splurge on U.S. technology shares in the first half of 2000. Just as stock markets were beginning to plunge that year, with the Nasdaq Composite Index falling 78 percent through October 2002, Alwaleed bought $400 million of Compaq Computer Corp. shares and $200 million of WorldCom Inc.

He also purchased shares of Amazon.com Inc. and DoubleClick Inc. as well as household names such as AT&T Corp., McDonald’s Corp. and Coca-Cola. The prince told Bloomberg News at the time that he was buying all of these stocks on the cheap.

Praise from Murdoch

As he spread his money around corporate America, Alwaleed won many friends. News Corp. Chairman Rupert Murdoch was among the 355 guests who gathered at the Plaza Hotel to honor the prince in November 2000 at an awards dinner thrown by the Arab Bankers Association of North America.

As he spread his money around corporate America, Alwaleed won many friends. News Corp. Chairman Rupert Murdoch was among the 355 guests who gathered at the Plaza Hotel to honor the prince in November 2000 at an awards dinner thrown by the Arab Bankers Association of North America.After the guests took their seats in the Grand Ballroom, Alwaleed entered the room with his retinue and walked to the head table, drawing applause. He sat next to Murdoch, and the two men chatted over a dinner of lobster tails and rack of lamb.

Then the media mogul took the podium to praise the Saudi royal for his investment in News Corp., at the time an Australian company that had U.S.-traded shares. From his initial News Corp. investments of a combined $600 million in 1997 and 1999 through that evening in 2000, Alwaleed had almost doubled his money.

“Very proud, we are, that Prince Alwaleed is one of News Corp.’s largest shareholders,” Murdoch said.

Selling Apple

After six tribute speeches, Alwaleed returned to the hotel’s Suite 537, decorated with gilded furniture, where journalists quizzed him about ill-timed investments he had announced about six months earlier.

After six tribute speeches, Alwaleed returned to the hotel’s Suite 537, decorated with gilded furniture, where journalists quizzed him about ill-timed investments he had announced about six months earlier.“We don’t see any further investments in the Internet,” Alwaleed said. “Many companies are going to go bankrupt.”

In 2002, the same year in which WorldCom went belly up, the prince deployed another $1 billion in three companies whose stock he already owned: AOL Time Warner Inc., Priceline.com Inc. and Citigroup.

Priceline.com was the only winner: The shares he’s held on to have jumped fourfold to about $175 million, based on data in Kingdom Holding documents.

The investor would be worth several billion dollars more today had he not chucked the bulk of his stake in Apple in 2005. He had poured $115 million into the computer maker in 1997. Under founder and CEO Steve Jobs, the company introduced the iPod four years later.

Returning to Saudi

At Alwaleed’s Hotel George V in Paris in November 2005, the prince told Bloomberg News his motive for selling his Apple stake.

At Alwaleed’s Hotel George V in Paris in November 2005, the prince told Bloomberg News his motive for selling his Apple stake.“The benefit of iTunes and all the good moves that Steve Jobs has done have already been put in the price,” Alwaleed said.

He was wrong. The rapidly selling iPod was followed in 2007 by the iPhone, which transformed mobile devices, and the iPad in 2010. The prince missed a sevenfold rally starting from the middle of 2005. His holding would have been worth about $6.75 billion as of today.

As Alwaleed was selling his Apple shares, he began moving money from the U.S. into Saudi Arabia, which itself was in transition. In 2005, King Fahd, who had ruled for 23 years, died at age 82, propelling Alwaleed’s uncle -- Crown Prince Abdullah -- to the throne.

“The prince made a commitment to the king,” Sanbar, 62, says. “He said, ‘Instead of having 80 percent of my wealth outside, I’m going to bring it here.’”

Kingdom IPO

In 2007, Alwaleed put together an initial public offering for Kingdom Holding on the Saudi stock exchange. The 240-page prospectus, which appeared on Kingdom Holding’s Web site only in Arabic, said the company’s listed assets had achieved lifetime annual returns of 19.9 percent through March 30, 2007.

In 2007, Alwaleed put together an initial public offering for Kingdom Holding on the Saudi stock exchange. The 240-page prospectus, which appeared on Kingdom Holding’s Web site only in Arabic, said the company’s listed assets had achieved lifetime annual returns of 19.9 percent through March 30, 2007.The figure included only shares held at the time, omitting money losers such as WorldCom that Alwaleed had already sold.

“These historical results do not represent all of the investments that Management has made during the relevant historical periods,” the prospectus said.

The prospectus contained one number that concerned potential shareholders, Sanbar says. Some 40 percent of its assets were in Citigroup stock, which was just starting to slip from its record high of $56.41 in December 2006. Kingdom Holding assured investors it would pare back the Citigroup stake.

“The answer was, we were going to start selling and shift to regional and Gulf investments,” Sanbar says.

Citigroup Crashes

Kingdom Holding’s stock jumped 20 percent on its first day of trading on July 29, 2007, giving the company a market value of about $20 billion. But Kingdom never sold its Citigroup shares as planned. From the IPO to the end of 2007, as credit markets tightened, the bank’s stock plunged by more than a third.

Kingdom Holding’s stock jumped 20 percent on its first day of trading on July 29, 2007, giving the company a market value of about $20 billion. But Kingdom never sold its Citigroup shares as planned. From the IPO to the end of 2007, as credit markets tightened, the bank’s stock plunged by more than a third.“Buy-and-forget can be deadly to a portfolio,” says Frederic Dickson, who manages $25 billion, including Citigroup shares, as chief market strategist at D.A. Davidson & Co. in Lake Oswego, Oregon.

As the deepening credit crisis sent Citigroup shares tumbling 77 percent in 2008, Alwaleed had one reason to cheer. At Microsoft’s annual CEO summit in May in Redmond, Washington, the prince finally got to meet his pen pal, Buffett.

During the event, a beaming Alwaleed posed with Buffett for a photo taken by the prince’s personal photographer. Buffett hammed it up for the camera, handing his black wallet to the prince as the flash went off.

Photo With Buffett

After the conference, Alwaleed sent Buffett a copy of the photo, and Buffett wrote back to thank the prince. In signing off, he continued their banter about collaborating.

After the conference, Alwaleed sent Buffett a copy of the photo, and Buffett wrote back to thank the prince. In signing off, he continued their banter about collaborating.“I hope we can come up with something in which we can work together,” Buffett said in the June 2008 letter.

Alwaleed could use some help from the Oracle of Omaha. In 2008, Kingdom Holding reported a net loss of $7.98 billion. That year, as the U.S. government injected $45 billion into Citigroup to save it, the prince began to buy more of the bank’s shares.

“At $3, you have to buy,” Alwaleed says. His purchases from 2008 and 2009 turned a profit as Citigroup shares rose to $4.61 on April 26.

While Kingdom Holding rebounded to a profit of $107 million for 2009, it also reported the unrealized loss of $3.53 billion that carried over from 2008’s rout. Bankler, the forensic accountant, says the profit could vanish, slashing the company’s market value and Alwaleed’s net worth, if even a small portion of those unrealized losses became permanent.

Fairmont, Four Seasons

“One of the factors of market value is earnings per share, and they didn’t take that hit,” Bankler says.

“One of the factors of market value is earnings per share, and they didn’t take that hit,” Bankler says.Alwaleed’s fortunes are improving this year. On April 19, Citigroup posted a first-quarter profit after two years of losses, and the next day, Kingdom Holding also reported a gain. But the company’s shares remain in the doldrums. Since its first trading day in 2007, Kingdom Holding’s stock has fallen 54 percent to 9.6 Saudi riyals on April 26.

“Alwaleed is a major player, always will be,” says Four Seasons CEO Isadore Sharp, who became fast friends with the prince after they met on Alwaleed’s yacht in 1994. “The markets are turning. Things are getting back on track.”

Alwaleed says he plans to take his hotel businesses public in the next few years. He bought his first stakes in Toronto- based Fairmont Raffles Holdings International and Four Seasons in 1994. Fairmont also runs the Plaza Hotel, which is jointly owned by Kingdom Holding and Israeli billionaire Isaac Tshuva’s Elad Properties.

Hotels made up 63 percent of the assets in the prince’s company in 2009, according to its year-end report.

‘He’s a Hotelier’

“He’s a hotelier,” Bankler says. “This is a hotel company.”

Alwaleed’s partners in Fairmont, which runs more than 90 hotels worldwide, include Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund and Colony Capital LLC, the Los Angeles-based buyout firm founded by billionaire Thomas J. Barrack.

The prince is in business with Gates at Four Seasons, which operates 83 hotels globally. Kingdom Holding and Gates’s investment company, Cascade Investment LLC, each hold 47.5 percent of the hotel management company. Sharp, who founded Four Seasons, retains a 5 percent stake.

Fairmont and Four Seasons may be ripe for an IPO as the recession eases and companies stop trimming travel expenses, says Smedes Rose, an analyst who covers hotels at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc. in New York.

Kingdom Tower

“Trends are turning much better for them, and you’d want to go public into the momentum of a recovering market,” he says. “Four Seasons has a lot of legs.”

“Trends are turning much better for them, and you’d want to go public into the momentum of a recovering market,” he says. “Four Seasons has a lot of legs.”Alwaleed says that within two years he also plans to hold an IPO for his Riyadh-based media company, Rotana Holding, which includes Arabic movie and music channels and a record label. In February, Murdoch’s News Corp. agreed to buy 9.1 percent of Rotana for $70 million.

The prince’s Kingdom Tower project in Jeddah, Saudi’s commercial hub on the Red Sea, faces several obstacles. The spike-shaped skyscraper anchors a project that includes shopping malls, a marina, hotels, villas and parks. Alwaleed, who says the tower will be completed in four to five years, plans to raise some of the $20 billion that the complex will cost from equity investors and the sale of Islamic bonds.

And he has hired Emaar Properties PJSC -- the Dubai-based contractor that erected Burj Khalifa -- to manage the project.

And he has hired Emaar Properties PJSC -- the Dubai-based contractor that erected Burj Khalifa -- to manage the project.“The beef is in Saudi Arabia,” Alwaleed says. “In 2010, we’re seeing ourselves coming out of it.”

Burj Khalifa opened in January, just after the Arab emirate went from being the world’s best-performing real estate market to the worst. Prices for apartments in the tower have dropped to less than half of their 2008 peak during the credit crackup.

$32.1 Billion Difference

Alwaleed may have an even tougher time filling his skyscraper in Saudi Arabia, says Saud Masud, head of Middle East research at UBS AG in Dubai. Masud says Saudi laws and customs, including restrictions on travel, women’s attire and the purchase of local securities by foreigners, deter visitors and businesses from entering the nation.

“It’s not going to be a straightforward build-it-and-they- will-come,” Masud says. “What the market needs now is affordable housing and not kilometer towers.”

As the prince rides in his GMC truck around the site of his Kingdom City residential development, he once again draws comparisons between himself and Buffett: The prince says they both buy undervalued assets. The offices of Kingdom Holding and Berkshire Hathaway have roughly the same square footage, and both companies have small staffs at their headquarters.

Pepsi Versus Coke

“I drink Pepsi; he drinks Coke,” Alwaleed says, with a laugh.

The biggest difference between the two men: The investor from Omaha is worth about $32.1 billion more than the Saudi prince. Alwaleed’s sluggish performance over the past decade hasn’t crimped his style, though.

In 2012, he’ll take delivery of a custom-fitted double- decker Airbus A380, becoming the first private buyer of the world’s biggest airliner. While he may not be the world’s richest man, he knows how to act like he is.

In 2012, he’ll take delivery of a custom-fitted double- decker Airbus A380, becoming the first private buyer of the world’s biggest airliner. While he may not be the world’s richest man, he knows how to act like he is.Source:

Bloomberg

Comments